Bird of The Week: Palila

Scientific Name: Loxioides bailleui

Population: Estimated at fewer than 680

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Trend: Decreasing

Habitat: Dry māmane forests on the island of Hawai’i.

About the Palila

One of Hawai’i’s endemic honeycreepers, the Palila lives in dry, open māmane forests high on the slopes of Mauna Kea. This species is a standout in an already unique group of island birds: Most Hawaiian honeycreepers spend their days seeking nectar and insects, gathering food using rather thin, straight or curved bills. But unlike species such as the ‘Ākohekohe and ‘Anianau, the Palila has a thick, finch-like bill.

Bulky Beak

The Palila’s bulky beak is perfectly suited for foraging in the endemic māmane tree. The yellow-breasted songbird uses its thick, hooked, sharp-edged bill to strip open the tree’s leathery seedpods and reach unripe seeds, the bird’s primary food source.

This bird’s survival and reproductive success depend on the reproductive success of the māmane. During drought years when the tree’s seed crop is low, most Palila do not attempt to breed. There is currently a severe drought in the region, suggesting another difficult year for this highly endangered bird.

Songs and Sounds

The Palila has a simple song and calls that include some rich notes resembling those of the finches such as the American Goldfinch.

Breeding and Feeding

Slow Breeder

The female Palila does most of the nest-building, constructing a cup of small sticks and leaves, usually high up in a māmane or sometimes a tree of another species. She lines her nest with grasses, then lays two, or sometimes one or three, eggs. The female incubates her clutch for a bit longer than two weeks. After the eggs hatch, both parents work to feed the growing young.

Palila eggs and nestlings develop slowly compared to many other songbirds, whose young generally fledge from 10 to 20 days after hatching. In contrast, most Palila nestlings spend at least 25 days in the nest, so remain vulnerable for longer to predators, harsh weather, and other dangers. Even after young Palila leave the nest, their parents continue to care for them for another 3-4 months, teaching them how to successfully forage on māmane pods.

This lengthy parental care period means that the Palila has a very low reproductive capacity, and a slow population recovery.

Māmane Muncher

Full-sized, but unripe, māmane seeds are this bird’s main food source. Palila acquire them by foraging at the tree’s branch tips, plucking the tough seed pods, pinning them with one foot, then ripping them open with the bill. When seeds aren’t available, Palila munch māmane flower buds or even young leaves or buds. Other foods are sometimes taken, but constitute a small portion of the diet. These include fruits of another endemic tree, the naio, and caterpillars – which are especially important protein source for their nestlings.

Region and Range

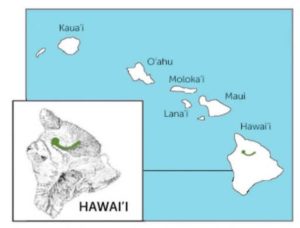

Palila were once found on O’ahu, Kaua’i, and across Hawai’i Island. Today, this species clings to life in a tiny patch of habitat of only about 25 square miles on the upper slopes of the Mauna Kea volcano on the Big Island. This remaining dry-forest habitat represents less than five percent of the Palila’s historic range.

Palila were once found on O’ahu, Kaua’i, and across Hawai’i Island. Today, this species clings to life in a tiny patch of habitat of only about 25 square miles on the upper slopes of the Mauna Kea volcano on the Big Island. This remaining dry-forest habitat represents less than five percent of the Palila’s historic range.

Three other Hawaiian honeycreepers, the ‘Akiapōlā’au, Hawai’i ‘Akepa, and ʻAlawī (Hawai’i Creeper) are also limited to the Big Island.

Conservation

Introduced species — plants and animals imported from other parts of the world — are this six-inch bird’s main challenge. Domestic sheep and goats were introduced at the end of the 18th Century and quickly spread, destroying and altering the native habitat. Mouflon sheep were introduced in the 1960s, further exacerbating destruction of the māmane forest. The over 200 years of habitat degradation caused by these non-native animals and by human development were major factors in the Palila’s decline.

Non-native predators are another problem: Cats eat Palila adults and nestlings, and rats can also sometimes take the birds or their eggs. In addition, Palila are highly susceptible to introduced mosquito-borne diseases such as avian malaria. For now, remaining Palila live at an elevation where mosquitoes and the malaria parasite are unable to successfully reproduce. With a warming climate, mosquitoes are moving up the mountains across the state, so this is likely to change in Mauna Kea’s subalpine forests.

Bringing back the Palila is one of the top priorities of ABC’s Hawai’i Program. To improve the forest and protect the bird, ABC works with partners like the Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Project to plant thousands of native trees each year and to remove non-native predators. We also work with partners to maintain a fence around most of the federally designated Palila Critical Habitat to keep out sheep and goats.

ABC also works with the Hawai’i Division of Forestry and Wildlife and the U.S. Geological Survey to provide annual population monitoring data on the Palila. The 2021 census estimated the population between 452-940 birds, and over the recent 23-year intensive monitoring period, there has been an 89% decline in the species.

ABC is dedicated to the survival of the remaining Hawaiian honeycreepers and the islands’ other endemic birds. As part of the Birds, Not Mosquitoes initiative, ABC works with partners on a large-scale effort aimed at curbing the islands’ non-native mosquito populations. To do this, the partners propose to deploy a naturally occurring bacteria as “birth control” to reduce mosquito numbers in high-altitude forest bird habitat across the islands.

In June 2023, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced the commitment of nearly $16 million in federal funding to restore populations of dwindling endemic Hawaiian songbirds, under the Hawaiian Forest Bird Conservation Keystone Initiative. Among the actions to be funded: expanded captive rearing programs for the most at-risk species; work to control and eradicate invasive mosquitoes that spread avian malaria; and translocation of bird populations to higher elevations, beyond the reach of mosquitoes. Another component of these programs is engagement with Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners and experts.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies have a huge impact on Hawai’i’s birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by telling lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC’s Action Center.

Our Hawaiian partners frequently need help with habitat restoration and other projects benefiting birds. If you live in or will be visiting Hawai’i and would like to volunteer, check the following Facebook accounts for opportunities: Kaua’i Forest Bird Recovery Project, Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project, and Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Project.

Source: American Bird Conservancy (abcbirds.org)