Bird of The Week: King Vulture

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Sarcoramphus papa

POPULATION: Unknown

TREND: Decreasing

HABITAT: Expansive areas of lowland forest and adjacent open areas.

The King Vulture is a clownish-looking bird with a serious mission: In most of its extensive tropical range, this species is the largest scavenging bird. The King’s smaller, more plentiful relations, including Black and Turkey Vultures, depend upon this heavy-billed bird to tear into larger carcasses first. The King only plays second fiddle to the Andean Condor in a few areas, such as northern Peru, where both species live side by side.

At 6.5 feet, the King Vulture’s wingspan is certainly impressive, but it doesn’t match up to those of the condors: The Andean Condor, wingtip to wingtip, can reach 10.5 feet; the California Condor is only slightly smaller.

Top of Their Line

Despite having larger cousins, the King deserves its royal moniker for at least three reasons: As mentioned before, it outranks other vultures of the Americas in size in most of the remote lowland forest and environs where it occurs. And its size, including its hefty bill, puts it at the top of the “picking order” — able to muscle its way into feeding frenzies and dig deeper into carcasses than other species sharing its habitats.

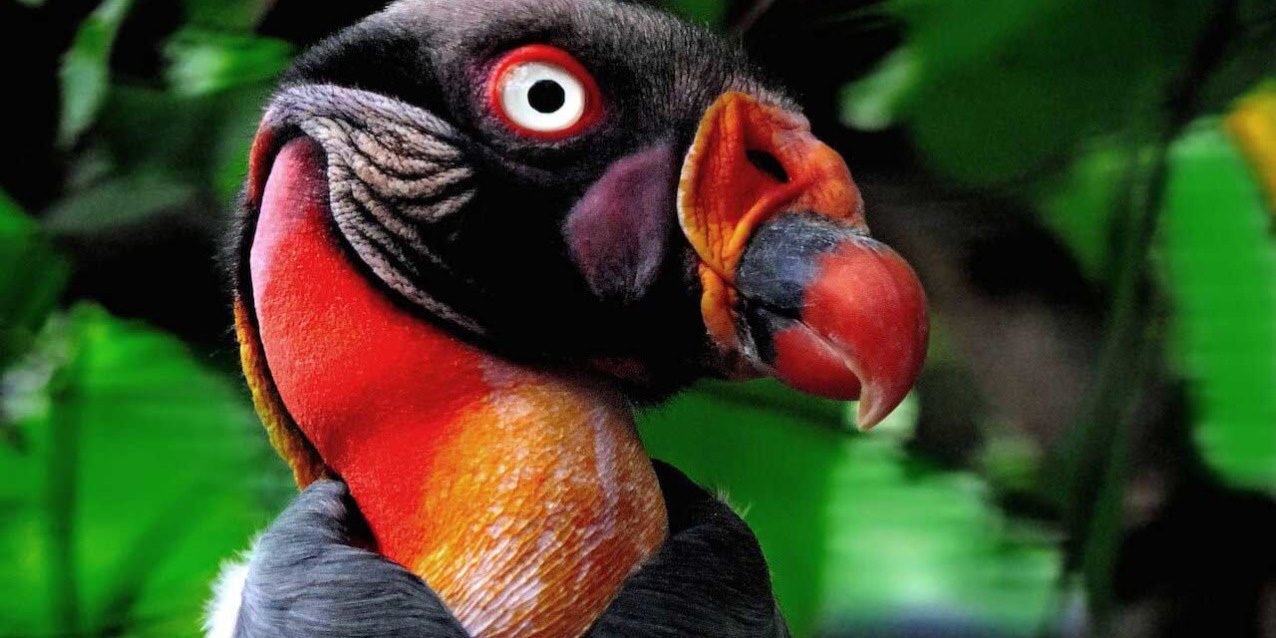

The King Vulture also wins the “beauty” prize for most colorful vulture. Adults sport multicolored, featherless heads that are a hodge-podge of peach-orange, yellow, red, and pink, all framed nicely by a charcoal feather neck ruff. Another eye-catching accent: the bird’s piercing white eyes, which are outlined by cherry-red orbital rings. These birds are striking in flight as well: Adult King Vultures can be easily identified from great distances, thanks to gleaming white backs, underparts, and underwing coverts fringed by black flight feathers. (At a distance, soaring Wood Storks are the birds most likely to cause confusion.)

Widespread but Generally Scarce

King Vultures occur from southern Mexico to northern Argentina and northern Uruguay. This range includes most of Brazil. In Central America, distribution is now spotty, with this majestic bird most frequent in remaining wilderness areas. For example, in Costa Rica, King Vultures are most reliably found in the remote Osa Peninsula in the south and the San Carlos River region near the border with Nicaragua.

King Vultures are mostly found in forested lowlands, but in the southern Andes they can occur at elevations up to 6,000 feet. The species is thought to be nonmigratory, but individuals travel long distances in search of food. While most frequently encountered in or over humid and semi-humid forest habitats, the King Vulture also occurs in regions with dry forest, usually where large areas of habitat remain. Although associated with forest, these birds also soar over and forage in open areas.

King Vultures have been documented emitting at least a half dozen harsh vocalizations at nest sites. Most are from nestlings and some by adults attending the young. These include growls, groans, screeches, and a noise like a cutting saw. Otherwise, while out and about, this bird is not known to vocalize.

Late to the “Party”

King Vultures cover large areas and tend to occur in low numbers, especially compared to some of their smaller relatives. But they have a special “seat at the table” at carcasses. For a study published in 1987 in the journal The Auk, researchers observed the goings-on at 217 animal carcasses in northern Peru, where five scavenging bird species vied for the spoils. These feeding assemblages might seem chaotic, but the study revealed a certain order that likely helps explain how these species coexist: Turkey Vultures, which likely have among the best olfactory senses in the family, often showed up first at carrion, holding sway over arriving, smaller Black Vultures, unless their numbers exceeded dozens. The Crested Caracara, not a vulture but an opportunistic follower, cautiously skirted the edges of the frenzies, visiting for leftovers after the main feeding. Arriving last were the largest birds — the King Vulture (which may not have a good sense of smell) and the even-larger Andean Condor. These birds brought their superior cutting equipment — their heavy bills — which allowed them to tear open large carcasses the other birds could not. For these larger meals, the smaller early arrivals had to wait on the sidelines until the giants had their fill.

Although King Vultures are best known as scavengers supreme, feasting on a wide variety of dead creatures from fish to monkeys to livestock, they have also been seen eating maggots, and also palm fruits. In addition, there are reports that these birds sometimes kill small lizards, wounded animals, and newborn livestock.

One-Shot Wonder

King Vulture pairs, like those of the Laysan Albatross, put all their energy into a single egg. Incubation and feeding duties are taken on by both female and male. King Vulture breeding remains rather poorly understood, in good part because the birds are stealthy nesters often in remote areas. The egg is laid in a secluded spot. Locations have included a simple scrape on the ground, a rotting stump or tangle, a large tree hole, a cliff ledge, and even in Mayan ruins. Parents incubate the egg for almost two months, and then the hatchling remains at the nest site until it fledges, after between two to three months, or longer.

Not only do King Vultures have only one shot at success — it takes them a long time to reach breeding age. Female Kings don’t reach adulthood for four to five years; males take longer, at five to six.

Saving Room for the King

Although still found in 20-plus countries and ranked as “Least Concern” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List, the King Vulture is declining in many parts of its range. Causes of decline likely include habitat loss and persecution, including unregulated shooting, capture, and poisoning. Along Mexico’s Pacific and Gulf coasts, the northern extent of this species’ range shrank dramatically over recent decades, and it has become scarce in many other regions with extensive forest clearing, including western Ecuador and southeastern Brazil.

ABC’s BirdScapes approach to bird conservation helps to protect habitats throughout the Americas, including forests harboring King Vultures as well as Neotropical migrant birds such as the Wood Thrush, Hooded Warbler, and Yellow-billed Cuckoo.

Source: American Bird Conservancy (abcbirds.org)