Bird of The Week: Evening Grosbeak

Scientific Name: Coccothraustes vespertinus

Population: 3.8 million

Trend: Decreasing

Habitat: Breeds in coniferous and mixed forests. Wanders widely during winter.

About

One Evening Grosbeak is a spectacular sight, but a flock of these big finches is unforgettable — an ever-shifting symphony of rich yellows, browns, and grays, set off by bright black-and-white accents. Although the females are less conspicuously colored, their size and large bills still make them standouts. In fact, the Evening Grosbeak’s genus name Coccothraustes means “kernel-cracker,” a nod to this bird’s powerful bill.

Early English settlers dubbed this species the “Evening” Grosbeak in the mistaken belief that it came out of the woods to sing only after sundown. French settlers gave it a more appropriate appellation: le gros-bec errant (the wandering big-bill, or grosbeak).

Like other winter finch species such as the Pine Siskin, Pine Grosbeak, and Purple Finch, the Evening Grosbeak is only an intermittent visitor to backyard feeders. In many years, it does not appear in some regions at all.

Irregular Irruptions

Evening Grosbeak flocks periodically move south when seed crops are less abundant than usual. These seasonal southern movements, or irruptions, are seen in many wintering boreal seed-eating birds, including the White-winged Crossbill and Red-breasted Nuthatch. Other northern birds such as the Snowy Owl irrupt in response to boom-and-bust cycles of their rodent prey.

People lucky enough to have Evening Grosbeaks visiting their feeders can be in for a major investment: A flock can consume hundreds of pounds of sunflower seeds over the course of a winter!

Songs and Sounds

Although the Evening Grosbeak is a noisy bird, constantly vocalizing with piercing calls and burry chirp notes, it does not produce complex songs to attract a mate or defend territory.

Breeding and Feeding

Making Moves

Evening Grosbeaks usually pair up before arriving on their breeding grounds. Since this species lacks a complex song, its courtship depends on mutual movement. The male performs a “dance” for the female, swiveling back and forth with raised head and tail and drooping, vibrating wings. Partners alternately bow to each other, and the male will offer food to his mate.

The female Evening Grosbeak builds her nest — a loose cup of twigs lined with softer grasses, pine needles, and lichens — in a tree or large shrub, 20 to 60 feet above ground. She lays two to four eggs, which she incubates for about two weeks. Her mate brings her food while she sits on the eggs, then both parents feed the nestlings. Young birds fledge about two weeks after hatching. This species has one or two broods per year.

Seeds make up the bulk of an Evening Grosbeak’s diet, especially seeds of boxelder and other maples, ash, locust, and other trees. This chunky songbird also feeds on tree buds, berries, small fruits, and sap. During the summer, the Evening Grosbeak adds insects to its diet, particularly spruce budworm larvae and other caterpillars, and aphids.

Region and Range

Grosbeaks Gaining (and Losing) Ground

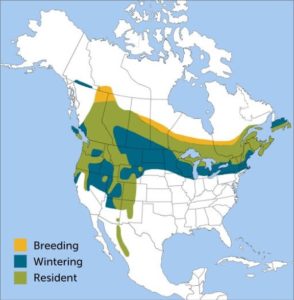

Evening Grosbeak breeds in mature and second-growth coniferous forests from the boreal forest belt down through the Rocky Mountains; it also occurs as a scarce resident of mountain forests in northwestern and central Mexico (small central Mexican population not shown on map). Depending on the year, wintering birds can be found well below the winter range indicated on the map at right. Three subspecies are recognized; birds of the western mountains have longer, thinner bills and darker female/juvenile plumage.

This species expanded its range rapidly across the eastern U.S. during the 20th century, possibly due to the increased planting of boxelder, a major food source, in cities. Unfortunately, the bird has become scarce in the East once again, and the specific cause is unknown.

Conservation

Behind the Grosbeak’s Decline

The State of the Birds 2022 Report has identified the Evening Grosbeak as a “tipping point” bird species — one that has lost 50 percent or more of its population from 1970 to 2019. Many other bird species, including the Allen’s Hummingbird, Chimney Swift, and Sprague’s Pipit, are in a similarly critical situation.

Potential causes of the Evening Grosbeak’s decline may include habitat loss, such as from tar sands development, hastened by accelerating climate change in boreal regions. Pesticides used to control spruce budworm, an important food for the Evening Grosbeak and other species such as Cape May, Blackpoll, and Bay-breasted Warblers, may also be a factor in its decline. In addition, many Evening Grosbeaks are killed by window collisions and by cars during the winter, when flocks may gather on roadsides to pick up road salt and grit.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have a huge impact on migratory birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by urging lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC’s Action Center.

Living a bird-friendly life can have an immediate impact on migratory birds in the United States. Doing so can be as easy as adding native plants to your garden, avoiding pesticides, and keeping cats indoors. To learn more, visit our Bird-Friendly Life page.

American Bird Conservancy and our Migratory Bird Joint Venture partners have improved conservation management on more than 8.5 million acres of U.S. bird habitat — an area larger than the state of Maryland — over the last ten years. That’s not all: With the help of international partners, we’ve established a network of more than 100 areas of priority bird habitat across the Americas, helping to ensure that birds’ needs are met during all stages of their lifecycles. These are monumental undertakings, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.

Source: American Bird Conservancy (abcbirds.org)